The basic functions of any reward and recognition system are to recruit, retain, develop, and motivate to perform. At the simplest level, reward and recognition systems work by satisfying the needs of those already performing in the volunteer role, and convincing those considering a volunteer role that some of their need will be satisfied through volunteering. In addition to motivating volunteer behavior by satisfying individual needs, reward systems should also be supportive of organizational goals. Check out these four steps towards a successful volunteer rewards system!

1. Productivity: A critical step in increasing the productivity of volunteers is task selection and assignment, because it is crucial for volunteer organizations to match the desires and abilities of the volunteer with assigned tasks as carefully as possible. Much of the potential reward for volunteers derives from successful task accomplishment.

2. Retention: Volunteers whose needs are unsatisfied will either withdraw from effective participation or leave for other organizations, where they perceive the potential rewards to be greater. By accurately identifying and addressing the specific needs of individuals and providing rewards and recognition that satisfy the need expectation, an effective reward and recognition system increases the likelihood that a volunteer will remain with the organization.

3. Morale and Espirit de Corps: People dislike ambiguity, and providing volunteers with specific objectives focuses their efforts. To the extent that individuals feel that they are performing well at an important task, their morale will be enhanced. As the leadership of an organization demonstrates concern for the volunteer through appropriate task management and performance recognition, the volunteer’s sense of personal satisfaction and willingness to participate will increase.

4. Organizational Changes: Volunteer organizations depend heavily on congruency between environmental and organizational goals. As they make changes, volunteer organizations must ensure that such changes are explained to their volunteers, who may have joined in support of what they perceive to be substantively different objectives. Because volunteers want to feel that their contributions are important and useful to society, any changes in organizational goals must be communicated to the volunteers to maintain both membership and productivity.

Reward systems drive behavior in certain directions and serve as excellent analytic foci for understanding the organizational culture. How do you plan on implementing a successful rewards system within your organization? Tell us in the comments!

Volunteer work has become increasingly responsible, sophisticated, and complex. There are many excellent reasons to write policies around voluntary action in nonprofit organizations. Such policies can be used to establish continuity, to ensure fairness and equity, to clarify values and beliefs, to communicate expectations, to specify standards, and to state rules. Read on as we share six important principles of writing volunteer policies.

Volunteer work has become increasingly responsible, sophisticated, and complex. There are many excellent reasons to write policies around voluntary action in nonprofit organizations. Such policies can be used to establish continuity, to ensure fairness and equity, to clarify values and beliefs, to communicate expectations, to specify standards, and to state rules. Read on as we share six important principles of writing volunteer policies.

Today’s blog post was written by Luci Miller, an AmeriCorps National Direct member at

Today’s blog post was written by Luci Miller, an AmeriCorps National Direct member at  in with my parents in Atlanta, Georgia.

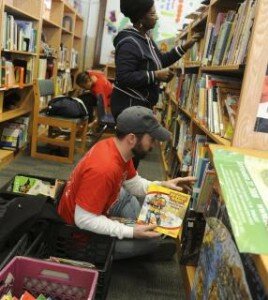

in with my parents in Atlanta, Georgia. At the end of my term, I was able to put my skills into action, while planning the Points of Light staff volunteer project at the Atlanta Tool Bank. I engaged over 25 volunteers successfully. It was amazing to see the skills I have been developing all year come to life!

At the end of my term, I was able to put my skills into action, while planning the Points of Light staff volunteer project at the Atlanta Tool Bank. I engaged over 25 volunteers successfully. It was amazing to see the skills I have been developing all year come to life! Effectively evaluating your volunteer program is important to ensuring the completion of your organization’s service goals. Evaluations can be done as often as necessary, but they should be a part of your volunteer program.

Effectively evaluating your volunteer program is important to ensuring the completion of your organization’s service goals. Evaluations can be done as often as necessary, but they should be a part of your volunteer program. evaluation, whether or not the program is supporting the organization’s goals.

evaluation, whether or not the program is supporting the organization’s goals.

on the grass, food trucks and farmers’ markets, art classes, performances and family festivals like the Salmon Return Celebration.

on the grass, food trucks and farmers’ markets, art classes, performances and family festivals like the Salmon Return Celebration. Points of Light’s two Seattle affiliates,

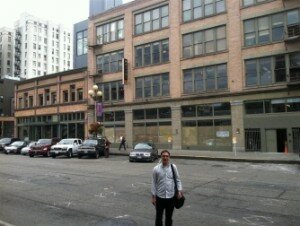

Points of Light’s two Seattle affiliates, And finally, the creation of the 30,000-square-foot Hub Seattle in the heart of Seattle’s Pioneer Square symbolized for me the importance and promise of the creation of community space. The Hub Seattle is bringing together entrepreneurs and investors to cultivate socially conscious ventures. This unique facility aims to educate innovative leaders, fund their ideas and incubate their social ventures. HUB Seattle anticipates housing more than a dozen social enterprises, with entrepreneurs sharing amenities and choosing from an assortment of work spaces. They aim to have the widest cross-section of world-changers anywhere.

And finally, the creation of the 30,000-square-foot Hub Seattle in the heart of Seattle’s Pioneer Square symbolized for me the importance and promise of the creation of community space. The Hub Seattle is bringing together entrepreneurs and investors to cultivate socially conscious ventures. This unique facility aims to educate innovative leaders, fund their ideas and incubate their social ventures. HUB Seattle anticipates housing more than a dozen social enterprises, with entrepreneurs sharing amenities and choosing from an assortment of work spaces. They aim to have the widest cross-section of world-changers anywhere.

nonprofit sector can create the strong, reliable, readily available matches every individual needs to kindle their civic leadership over a lifetime.

nonprofit sector can create the strong, reliable, readily available matches every individual needs to kindle their civic leadership over a lifetime. All of these higher education leaders were struggling to ensure high quality and depth in their offerings, while including the broadest possible spectrum of students. They were grappling with both the increasing costs of college and how to fully integrate national service resources into the community college or university experience. They raised the question of how we might include service as a way to reduce student debt.

All of these higher education leaders were struggling to ensure high quality and depth in their offerings, while including the broadest possible spectrum of students. They were grappling with both the increasing costs of college and how to fully integrate national service resources into the community college or university experience. They raised the question of how we might include service as a way to reduce student debt.

kids. The spark ignited a movement of caring families and volunteers. Portland is full of civic vitality and sparks that have been nurtured into bold flames of leadership and citizen engagement. How can we help provide the civic networks and support systems that form the sturdy matches of ignition and light to propel Emily, Eric and Dani?

kids. The spark ignited a movement of caring families and volunteers. Portland is full of civic vitality and sparks that have been nurtured into bold flames of leadership and citizen engagement. How can we help provide the civic networks and support systems that form the sturdy matches of ignition and light to propel Emily, Eric and Dani? A company that volunteers is a happier and better company, but that is only a small part of the picture. The support and encouragement that an employer gives to its employee’s volunteer activity can make a world of difference to their outcome! From something as simple as a kind word to an elaborate partnership with a local nonprofit organization, there are many ways employers can encourage volunteering among their staff. A variety of approaches can be utilized to reinforce or complement one another and suit the needs of the company. Read on to find an approach that is right for your organization.

A company that volunteers is a happier and better company, but that is only a small part of the picture. The support and encouragement that an employer gives to its employee’s volunteer activity can make a world of difference to their outcome! From something as simple as a kind word to an elaborate partnership with a local nonprofit organization, there are many ways employers can encourage volunteering among their staff. A variety of approaches can be utilized to reinforce or complement one another and suit the needs of the company. Read on to find an approach that is right for your organization. Endorsement

Endorsement My son, Vinson, is a great enthusiast for earning badges and pins of any sort, so we became devotees of the Junior Ranger program as we traveled through the national parks this summer. To earn his badges, we identified sage brush, learned what Sitting Bull did during the Battle of the Little Big Horn (stayed with the women and children), and discovered how long it took to carve the figures on Mount Rushmore (14 years).

My son, Vinson, is a great enthusiast for earning badges and pins of any sort, so we became devotees of the Junior Ranger program as we traveled through the national parks this summer. To earn his badges, we identified sage brush, learned what Sitting Bull did during the Battle of the Little Big Horn (stayed with the women and children), and discovered how long it took to carve the figures on Mount Rushmore (14 years).

The preservation of a special place like Crater Lake seems providential. But, it took three decades of advocacy and citizen leadership to make it happen. In 1870, when William Gladstone Steel was just a schoolboy, he unpacked his sandwich from its newspaper wrappings. As he ate, he read an article about an unusual lake in Oregon with startling blue water surrounded by cliffs almost 2,000 feet high. (So, perhaps it was providential). He first visited Crater Lake 15 years later and was so moved by its beauty, he began his tireless volunteer advocacy to have it preserved forever as a public park. Steele’s proposals to create a national park met with much argument from sheep herders and mining interests. He persisted and, in 1902, Crater Lake became a national park.

The preservation of a special place like Crater Lake seems providential. But, it took three decades of advocacy and citizen leadership to make it happen. In 1870, when William Gladstone Steel was just a schoolboy, he unpacked his sandwich from its newspaper wrappings. As he ate, he read an article about an unusual lake in Oregon with startling blue water surrounded by cliffs almost 2,000 feet high. (So, perhaps it was providential). He first visited Crater Lake 15 years later and was so moved by its beauty, he began his tireless volunteer advocacy to have it preserved forever as a public park. Steele’s proposals to create a national park met with much argument from sheep herders and mining interests. He persisted and, in 1902, Crater Lake became a national park.