Today’s blog post originally appeared on the Points of Light blog site on August 21.

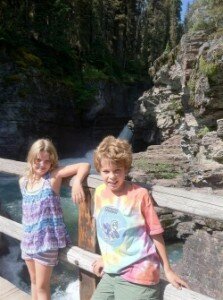

Michelle Nunn reflects on her families experiences at the national parks this summer.

My son, Vinson, is a great enthusiast for earning badges and pins of any sort, so we became devotees of the Junior Ranger program as we traveled through the national parks this summer. To earn his badges, we identified sage brush, learned what Sitting Bull did during the Battle of the Little Big Horn (stayed with the women and children), and discovered how long it took to carve the figures on Mount Rushmore (14 years).

My son, Vinson, is a great enthusiast for earning badges and pins of any sort, so we became devotees of the Junior Ranger program as we traveled through the national parks this summer. To earn his badges, we identified sage brush, learned what Sitting Bull did during the Battle of the Little Big Horn (stayed with the women and children), and discovered how long it took to carve the figures on Mount Rushmore (14 years).

We talked to lots of volunteer park service rangers who helped fill us in on the key, elusive answers to the Junior Ranger challenges. The successful completion of each booklet was rewarded not only with a badge, but also a swearing-in ceremony. Vinson was led, often by a volunteer ranger, in a pledge of re-commitment to our national parks and to the preservation of our nation’s special places and spaces: “As a Junior Ranger, I promise to teach others about what I learned today, explore other parks and historic sites, and help preserve and protect these places so future generations can enjoy them.” Thus, the National Park Service is cultivating the next generation of volunteers and advocates for conservation.

Our National Park System of 397 extraordinary geological, historical and cultural wonders was built upon the  passionate advocacy of citizen activists like Ferdinand V. Hayden, Yellowstone’s first and most enthusiastic advocate, and John Muir, founder of the Sierra Club and champion of Yosemite. As documentarian Ken Burns pointed out, “You’d be hard pressed to find something that was a purer expression of the democratic impulse, in setting aside land, not for the privileged, not for the kings and nobility, but for everybody. For all time.” This extraordinary heritage was created by citizen and volunteer leaders and it continues to be protected by a network of volunteers. The National Park Service has 22,000 employees, but ten times as many volunteers – 221,000.

passionate advocacy of citizen activists like Ferdinand V. Hayden, Yellowstone’s first and most enthusiastic advocate, and John Muir, founder of the Sierra Club and champion of Yosemite. As documentarian Ken Burns pointed out, “You’d be hard pressed to find something that was a purer expression of the democratic impulse, in setting aside land, not for the privileged, not for the kings and nobility, but for everybody. For all time.” This extraordinary heritage was created by citizen and volunteer leaders and it continues to be protected by a network of volunteers. The National Park Service has 22,000 employees, but ten times as many volunteers – 221,000.

My family enjoyed national parks ranging from Glacier to the Badlands to Mount Rushmore. At each park, I was struck by the constellation of volunteers, friends groups and private donations that support the National Park System. There are young people serving as volunteer Rangers, seniors who live in state and national parks as resident volunteers, and tens of thousands of volunteers who clear trails, fight fires, teach classes and help interpret the rich history and ecology of the parks.

The preservation of a special place like Crater Lake seems providential. But, it took three decades of advocacy and citizen leadership to make it happen. In 1870, when William Gladstone Steel was just a schoolboy, he unpacked his sandwich from its newspaper wrappings. As he ate, he read an article about an unusual lake in Oregon with startling blue water surrounded by cliffs almost 2,000 feet high. (So, perhaps it was providential). He first visited Crater Lake 15 years later and was so moved by its beauty, he began his tireless volunteer advocacy to have it preserved forever as a public park. Steele’s proposals to create a national park met with much argument from sheep herders and mining interests. He persisted and, in 1902, Crater Lake became a national park.

The preservation of a special place like Crater Lake seems providential. But, it took three decades of advocacy and citizen leadership to make it happen. In 1870, when William Gladstone Steel was just a schoolboy, he unpacked his sandwich from its newspaper wrappings. As he ate, he read an article about an unusual lake in Oregon with startling blue water surrounded by cliffs almost 2,000 feet high. (So, perhaps it was providential). He first visited Crater Lake 15 years later and was so moved by its beauty, he began his tireless volunteer advocacy to have it preserved forever as a public park. Steele’s proposals to create a national park met with much argument from sheep herders and mining interests. He persisted and, in 1902, Crater Lake became a national park.

American Pulitzer Prize-winning author Wallace Stegner wrote, “National parks are the best idea we ever had. Absolutely American, absolutely democratic, they reflect us at our best rather than our worst.” To sustain this extraordinary American legacy for all people and all time, the national parks depend on the next generation to volunteer our time, donate our money, and speak up to expand and preserve our country’s extraordinary parks. We need those Junior Rangers to take their vows to heart.